One thing that irritates me about how data modeling is taught is that it almost completely ignores organizational and political dynamics. For technical work in general, you can ignore these at your peril. Sadly, many do and only realize later that having a better situational awareness of the organization and the people they work with would have paid dividends and led to a higher success rate. The goal of this chapter is to give a data modeler the mental framework to (hopefully) succeed within their organization.

This chapter used to exist as a series of articles in this Substack, and is one of four chapters that close out the book in Part 3. Over the last few weeks, I have gone through the painful process of organizing, consolidating, editing (yes, I use em-dashes in the final edits cuz that’s the publishing standard), and reorganizing these ideas. I think this chapter captures what I’ve been trying to express in these various articles, and I’m pretty happy with the result of this 25 page tome. The advice I really wish I would have gotten earlier in my career.

More chapters will be dropping very soon as I’m finalizing the editing process. I don’t expect these chapters to change much between now and when the book is published. But if you find any errors, please let me know so I can incorporate those into the final manuscript.

Thanks,

Joe

“The major problems of our work are not so much technological as sociological in nature.”

— Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister, Peopleware

Not much has changed since the 1980s when Peopleware was first published. The story of data modeling cannot be told without understanding how people interact within organizations. Work is a highly sociological phenomenon, yet for some reason, it is an underserved topic in data modeling.

In my own experience, I’ve seen countless tech and data initiatives succeed or fail based not on the technical acumen of the practitioners but on the organizational dynamics surrounding them. The classic trap many practitioners fall into is believing their technical expertise will exempt them from interacting with “the business” or shield them from the whims and decisions of the broader organization. It’s happened to me many times, thinking my smarts and skills were enough. I’ve learned the hard way that many data initiatives, particularly data modeling, which can be very time-consuming, are at risk because the teams lack the situational awareness and organizational willpower needed to accomplish their goals. I believe this is one of the most pivotal chapters in the book, as ignoring it will likely lead to failure in your data modeling journey.

A discussion of data modeling is incomplete without discussing its impact on people, organizations, and architecture. In the spectrum of people, process, and technology, people are paramount. You can be as technical as you wish, but understanding how to navigate organizations and models alongside your organization’s architecture is crucial to success. In my experience, people and organizational issues sink more IT projects, data modeling or otherwise, than anything else. Let’s look at one infamous example.

Target Canada’s $7 Billion Failure

A classic case study of organizational problems disguised as technical ones is the spectacular dumpster fire of Target Canada’s failed expansion in the early 2010s. Target operated conservatively and methodically in the United States. Then Target decided to expand into Canada. In the case of Target Canada, they chose a big-bang market entry, opening well over 100 stores in a single year on brand-new systems, with new teams and new suppliers, and with no local operating history. The reason? In 2011, Target purchased the leasehold rights of defunct Canadian retailer Zellers for $2 billion. Unfortunately for Target, the lease deal set demanding, compressed timelines to open three new distribution centers and convert the stores into Target Canada stores, all in less than 2 years. Never mind that constructing one distribution center often takes around two or more years.

That aggressive, real estate-driven timeline became the de facto project manager. New people were severely undertrained and worked under immense time pressures. In the rush, the item master—the backbone of retail data—was hastily and inaccurately populated, with inconsistent units, packaging hierarchies, and identifiers that didn’t match those on the pallets. It only got worse. Shoppers received advertisements for products that weren’t in stock in stores, even though distribution centers were overstocked with assortments that didn’t fit local demand.

Underneath this chaos sat a dysfunctional tangle of organizational dynamics. Junior staff who lacked the authority to push back on bad data often handled supplier onboarding. Validations that should have blocked flawed SKUs were treated as speed bumps rather than gates. Replenishment forecasting tools went live without the historical data they require to behave sensibly. Because it was Target, the forecast was literally as naive as “Whatever Zellers sold, just double it.” Different groups optimized for various goals: merchants for launch count, supply chain for flow, and stores for in-stock metrics. Predictably, people found ways to bypass controls to make their particular numbers look better. None of this can be blamed on data or software failure. Misaligned ownership, incentives, and sequencing produced systemic data defects.

For data modelers, the lesson is not “pick a better tool.” Instead, it’s “design the social contract around the data model.” In Target Canada’s case, hindsight suggests treating the item master as a governed interface, not a disposable spreadsheet, where canonical units, packaging levels (each/inner/case/pallet), price zones and currencies, and required fields are enforced at write-time. Instead of using lease dates as the go-live date, ensure your data is ready for production by setting explicit quality bars for your highest-velocity SKUs and conducting end-to-end scans that reconcile physical labels to digital records. Give named business owners real accountability and the power to control data quality and modeling. And if your forecasting and inventory planning systems need history, start small and prudent so you can build it correctly.

One bad decision or one bad table didn’t cause Target Canada’s downfall. Instead, failure emerged when organizational and power structures, misaligned incentives, and speed collided with fragile data foundations. That’s the core theme of this chapter. Data models live inside organizations, and when the organization is misaligned, the data will tell you first in your apps, dashboards, or AI models, and then in reality.

A Closer-to-Home Failure: The Customer 360 Project

Target Canada is dramatic, but organizational failures happen at every scale. A friend joined a mid-sized company six months into their “Customer 360” initiative—a project to create a unified view of customers across Sales, Marketing, and Support. The technical approach was sound: consolidate customer data from Salesforce, Marketo, and Zendesk into a single warehouse.

Given what you just read, you shouldn’t be shocked that what killed the project wasn’t technology. It was that Sales and Marketing couldn’t agree on what a “customer” meant. Sales counted only closed-won accounts. Marketing counted anyone who’d filled out a form. Support counted anyone with a ticket. Each department’s bonus structure depended on their definition, and no one had the authority to override them. The data modeling team spent eight months in meetings trying to negotiate a unified definition while the project budget drained away.

The project was eventually cancelled—not because the data model was wrong, but because no one had secured executive alignment on definitions before starting the technical work. The data team became the scapegoat for “failing to deliver,” but the real failure was organizational: starting the “how” before resolving the “who” and “why.” My friend learned to never begin modeling without first documenting who owns the definitions and who has the authority to resolve disputes.

Theory vs. the Real World

“In theory, there’s no difference between practice and theory, but in practice, there is…”

— Yogi Berra

The organizational aspects of data modeling are often overlooked in the books and articles I’ve read. They instead teach technical data modeling tactics, assuming it happens in a vacuum. It’s like learning to box by watching instructional videos and hitting a punching bag. You’re learning movement, but you’re not getting punched in the face and developing real-world boxing awareness. Sadly, most data modeling efforts stall or fail because the real-world organizational aspects are ignored. Data modeling is a full-contact sport.

Of course, you’ll need to build or maintain a data model. But your job is much more than that. Your job will be a mix of practitioner, salesperson, and servant. But before you get to data modeling, there are often roadblocks. People need to understand why they should invest in data modeling, why they should collaborate with you on this initiative, and what matters to them. Especially in today’s organizations, people are pressed for time and budget. Most people are overworked and have little patience. Unless you can show them why they need to pay attention to data modeling and what’s in it for them, your progress will be stalled.

Data modeling theory paints a picture of a sterile, top-down exercise within a neat, orderly organization. Ideas and concepts are clearly understood, articulated, and always in sync. Data modeling is as simple as bringing people together for a series of workshops where they dispense everything you need, and you trot off to create the perfect data model. If only things were that easy.

While theory provides a useful starting point for understanding how things should be, it’s essential to recognize how it intersects with the real world. And the real world is a tough and unpredictable place. No matter how hard you try, applying theory to the real world will be hampered and challenged in ways that will surprise and frustrate you.

Let’s briefly look at some places where data modeling theory often gets a reality check:

- Ivory Tower Modeling. Data modeling is prescribed as a top-down exercise of gathering requirements from eager stakeholders, understanding every domain, and designing a pristine data model. What usually happens is you’re reverse-engineering some arcane, undocumented system, trying to decipher poor-quality data, and modeling under deadline pressure with incomplete information. Business rules are fuzzy and often undocumented. Stakeholders contradict each other. Requirements shift halfway through the project. For example, I once spent three weeks modeling an “order” entity only to discover that “order” meant something completely different in the warehouse system (a pick list) than in the e-commerce system (a customer transaction). Nobody told me because nobody realized they were using the same word for different things.

- Every data model is a political artifact. It reflects who had influence, what got prioritized, and what got ignored. These political dynamics are influenced by factors such as team communication, company strategy, technical debt, internal politics, and even personal relationships or vendettas. The Marketing VP who championed the new attribution model will fight to keep their preferred definition of “conversion” even when it’s demonstrably inconsistent with reality—because their bonus depends on it.

- One-size fits all. All too often, data modelers want to use their pet approach for every situation, regardless of whether it’s a good fit. Instead of viewing a data model as a singular approach, understand how different models serve diverse needs within an organization. This is the essence of Mixed Model Arts. A star schema that works beautifully for BI dashboards may be entirely wrong for a real-time recommendation engine. The data modeler who insists on one approach for both will fail at one—or both.

- Constraints and compromises are normal. Every situation is different and has its constraints. You might choose a textbook-level data modeling approach that, if implemented, would take several years. Then, you realize that due to time, budget, or resource constraints, you’ll need to make compromises and take shortcuts. The “right” way to model your product catalog might require a 9-month normalization effort. The business needs results in 3 months. You’ll need to accept some denormalization now and plan to refactor later—if “later” ever comes.

- Focusing only on tools and technology. The temptation is to reach for the closest tool and start building. The fixation on tools might distract from talking with people, understanding their world, and building a data model that works for them. A primary goal of data modeling is to achieve a shared understanding of the data within the organization. Especially for non-technical individuals, discussions about technology can be a significant distraction and turnoff. I’ve watched data engineers spend weeks evaluating whether to use dbt or regular SQL, while the actual stakeholders couldn’t even agree on what “revenue” meant. The tool choice was irrelevant; the conceptual alignment was everything.

As you can see, data modeling relies on situational and social awareness, not just knowledge of a particular modeling approach or tool.

The Gravity of Conway’s Law

“…organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.”

— Melvin Conway

In 1968, when computing meant giant mainframes and punch cards, Melvin Conway published a paper called “How Do Committees Invent?” He couldn’t have known it then, but his central observation would become a foundational law for technology and system design, eventually bearing his name: Conway’s Law.

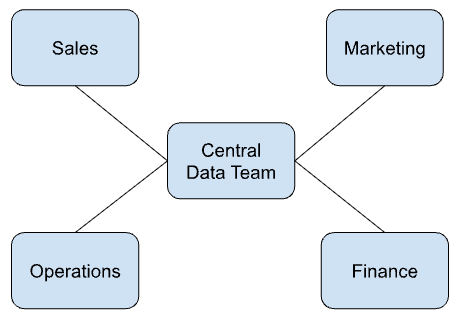

Conway’s Law states that organizations design systems that mirror their communication structure. Here, the org chart is “shipped” to the systems and architectures within the organization. The systems and data a company creates will reflect how its teams are organized and how they communicate. If the company is centralized and top-down, this creates hierarchical, siloed communication and systems. By contrast, a flat, decentralized organization will support less rigid, more open communication patterns.