Editor: The response to our new AI for Science agenda has been cautiously positive! We’ll also be featuring essays and approachable analysis for AI Engineers, in this dedicated feed — which you can opt in/out of on your account!

One struggle we’ve had: approximately NONE of us love the “AI for Science” moniker. We are excited to launch our Science section with Melissa Du, who proposed a useful taxonomy framework for thinking about how money and talent are funneling into 2-3 main approaches… and how they combine in a coherent plan for progress. By coincidence, she introduces many of our upcoming guests on the Science pod!

We’ve witnessed the meteoric rise of LLMs over the past 5 years. Through scale alone, the models have grown from naive stochastic parrots into entities we credit with agency and emotional depth. 66% of physicians use AI in the clinic; 47% of software developers rely on AI coding assistants daily (surprised this number isn’t higher…). 79% of law firms report AI adoption in document review. AI has nearly mastered language and humanity’s digitized knowledge.

When Dario Amodei published Machines of Loving Grace in 2024, he promised that AI would eliminate all bodily and mental ailments, resolve economic inequality, and create material abundance. But these aren’t exclusively language problems. Curing cancer, designing new materials, and solving energy will require AI that can interface with and predict the physical world, not just reason about text. Modern day AI for science discourse largely conflates progress in language models with progress in scientific modeling more broadly. And while the former will certainly accelerate our capacity to understand the natural world, the field of scientific modeling has had its own tribulations and successes predating the launch of ChatGPT.

Dario himself gestures at this distinction in his manifesto. He writes that AI can accelerate the eradication of disease by “making connections between the vast amount of biological knowledge humanity possesses” and “developing better simulations that are more accurate in predicting what will happen in humans.” He’s describing two different types of AI models.

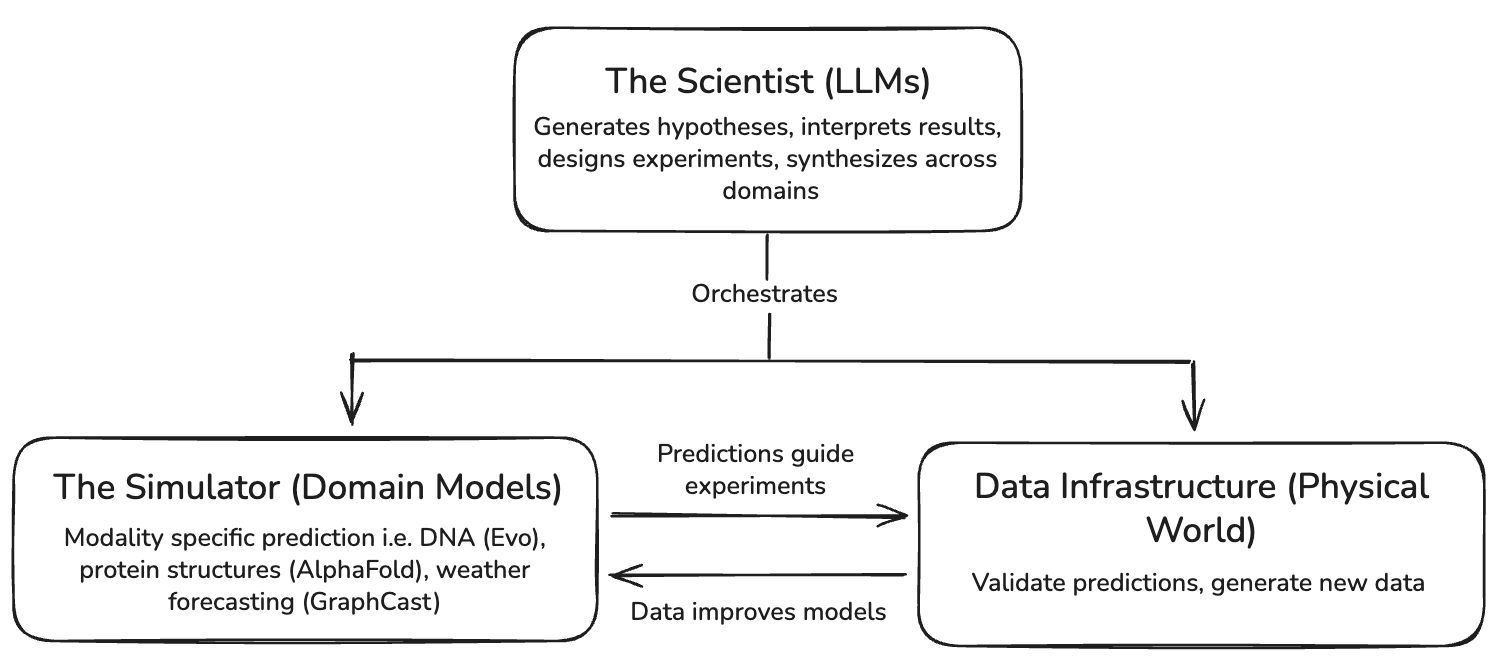

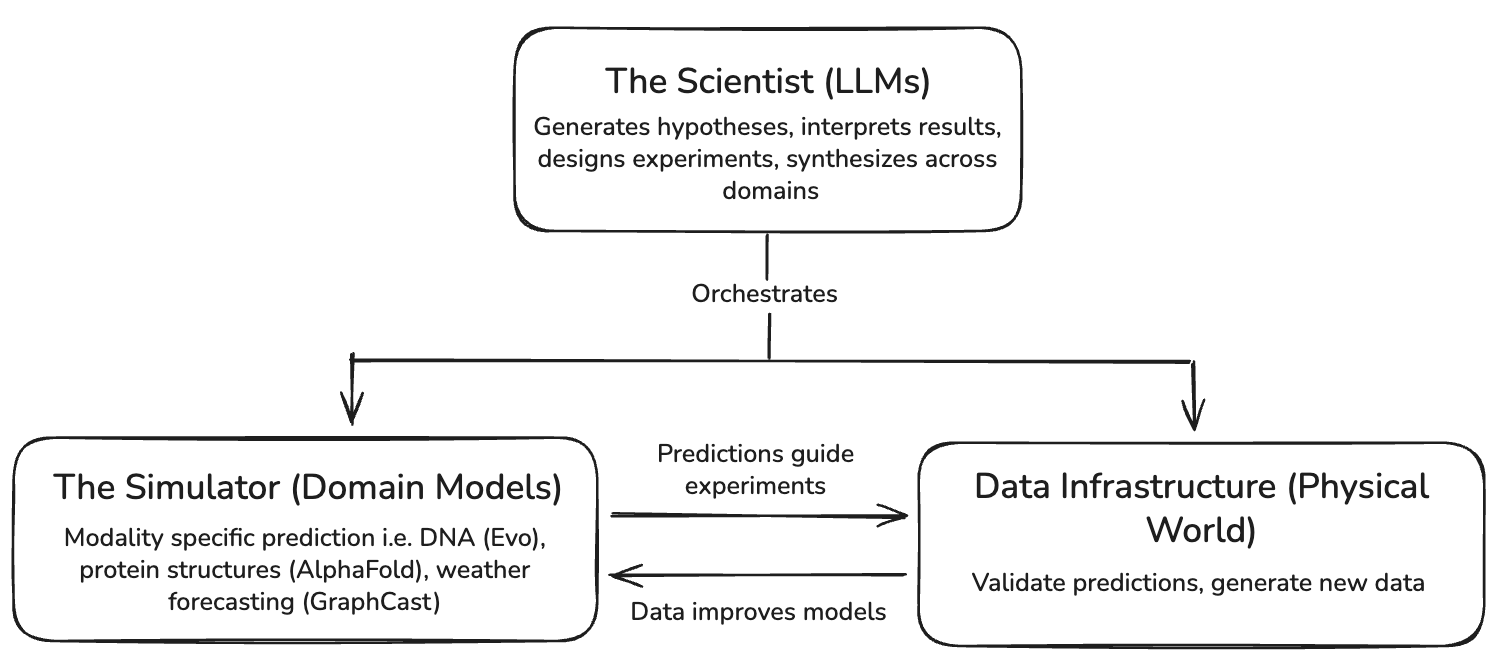

The first reviews literature, draws deep connections across studies, generates hypotheses, designs experiments, and updates its priors. It excels at reasoning, digesting large corpuses of knowledge, and keeping many ideas in working memory—precisely the areas where LLMs excel. With all due respect to the academics (I identify as one myself), we’ll call these models the scientists.

The second learns dynamics directly from data. It predicts outcomes within specific physical domains and learns structure that language alone cannot represent. We’ll call these models our simulators.

Scientists (LLMs) and simulators (domain models) are different programs within ML research that require distinct talent pools and data infrastructure, and they must work together to produce coherent models of the world. The full stack for AI-driven scientific discovery looks like this:

The capacity for LLMs to accelerate (and eventually replace) scientists cannot be overstated. OpenAI recently published a blog post demonstrating how ChatGPT could be plugged into a wet lab loop to accelerate a molecular cloning protocol. Anthropic has rolled out a suite of features for biologists that integrate Claude with existing platforms like Pubmed (paper repository), Benchling (experiment tracking), and 10x Genomics (single cell and spatial analysis).

These types of integrations are examples of giving LLMs tools for accomplishing real-world tasks, exactly the thesis undergirding the rise of agents. In these cases, OpenAI and Anthropic have provided their chatbots with hands to run wet lab experiments and access existing data platforms, but the past two years have seen the rise of magic blackboxes for search (Exa, Perplexity), document processing (Reducto), browser use (BrowserBase), etc, all of which are arguably more targeted towards agent than human use.

The blackbox tools that are necessary for LLMs to be effective in scientific discovery go beyond software. We’ll need abstractions for scientists to measure physical systems–automated laboratories, programmable in situ monitoring systems, and the like (data infrastructure). We’ll also need blackboxes for understanding and predicting the behavior of physical systems, which offer a fidelity to the world that language alone cannot capture (simulators).

Physics is simple, biology is complex

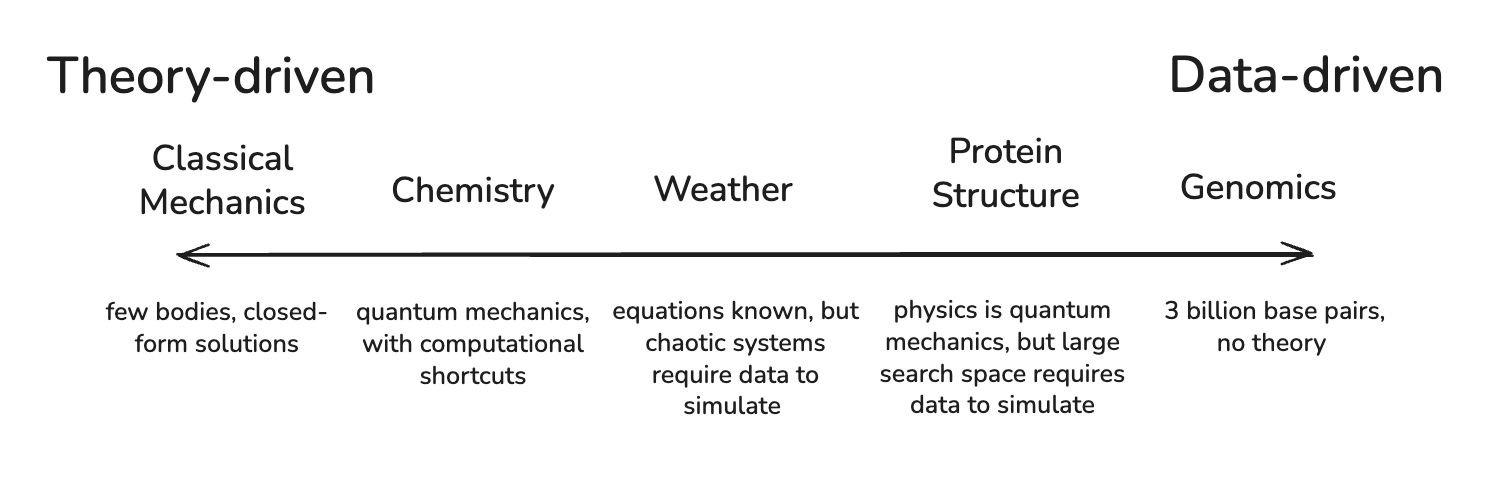

Why are simulators valuable? The core distinction between scientists and simulators, per our definition, is the reliance on text and reasoning as opposed to the reliance on domain-specific foundation models. Reasoning is sufficient when a domain has enough theoretical structure to support chain-of-thought derivation, but when theory is lacking, we require models that can learn directly from the data. The question of when this transition happens points to a deeper tension at the heart of scientific modeling: when can you derive predictions from theory and first principles, and when do you have to build models that pattern-match from empirics?

Silicon Valley loves “first-principles thinking,” and, as it happens, so do academics. Everything is derivable from first principles. Chemistry emerges from physics, biology from chemistry, cognition from biology. If you encode the fundamental laws and apply enough computation, everything can be simulated.

This is true! But unfortunately not as helpful for simulation as we’d like. Everything is atoms, but modeling atoms quickly becomes computationally intractable:

- The equations of quantum physics define how electrons interact, but our computers can only solve them on the order of tens of atoms.

- The next layer up is density functional theory (DFT), an approximation for electron clouds that scales to hundreds of atoms.

- Then, we replace our electron interactions altogether with force fields — the basis of classical molecular dynamics — which takes us to millions of atoms…

Every time we’ve hit a wall of complexity, we’ve developed new ways to measure systems and new abstractions and rules that enable us to reason about them. Rule-based simulation has given us countless early successes. Numerical weather prediction extended reliable forecasts from one day to seven by relying solely on fluid dynamics. Every transistor on every chip is simulated from Maxwell’s equations before fabrication.

But theory-driven simulation only works when the system permits elegant compression. Physics discovered that you don’t need to track 10²⁵ individual molecules to predict how a gas behaves; temperature and pressure are sufficient for prediction. A handful of forces and symmetries are sufficient to parametrize the properties of gasses, the motion of planets, the behavior of circuits.

The same is not true for biology. Or at least, we’ve yet to find an equivalent shortlist of parameters. The genome is three billion base pairs with complex regulatory logic. Expression patterns change depending on the cell cycle, tissue types, and the local chemical environment. A typical human cell contains roughly 10 billion protein molecules engaged in somewhere between 130,000 and 650,000 distinct types of protein-protein interactions. And unlike the molecules in a gas, the specific identities of the molecules matter. The specific transcription factors, regions of DNA, molecules, and interactions between them could determine whether a cell becomes cancerous. The microscopic details can't be averaged away.

from: Steve Jurvetson. Seriously… watch and realize this is happening in your body!

Biology has accepted certain theories—genetics, the Central Dogma, evolution—but these are descriptive, and lack the computational precision to power predictive engines. Thus, biology is traditionally taught as a dull exercise in memorization, the aggregation of never-ending facts, with very few unifying frameworks on which to perform inference or computation.

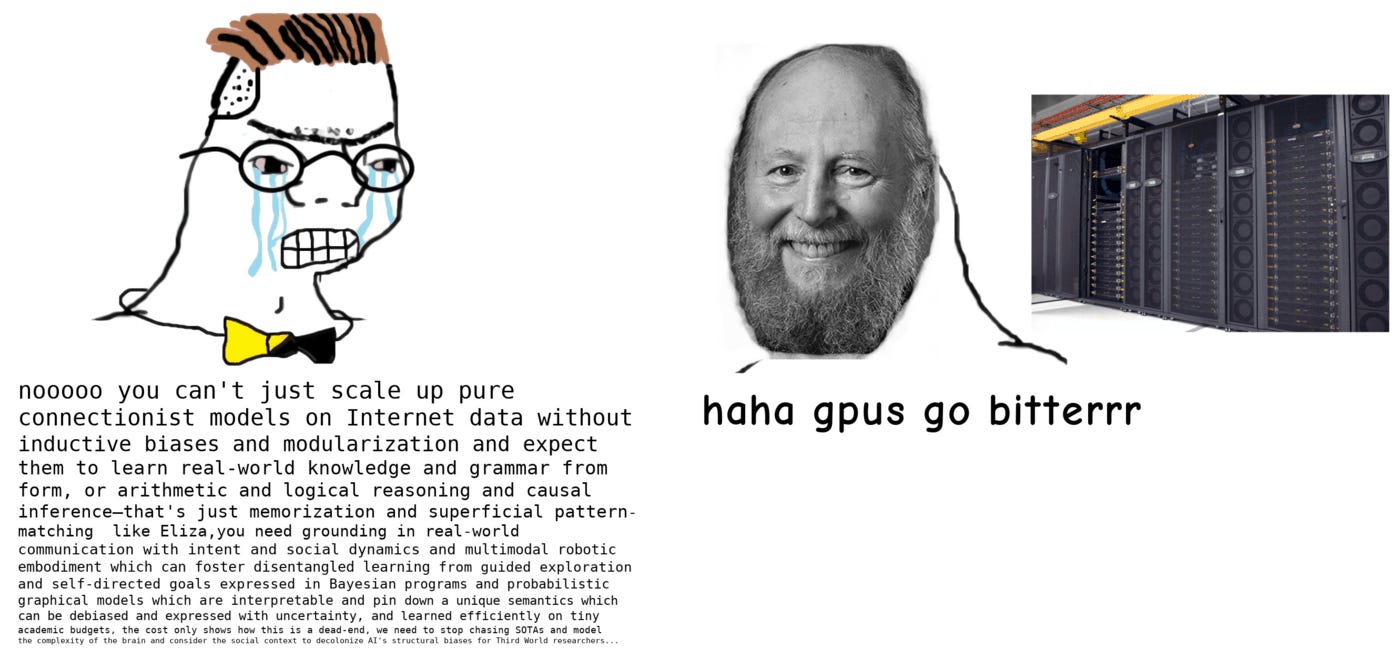

Chomsky, a linguist who spent his career developing the theory behind language, embodied the failure mode of theoreticians with respect to the field of linguistics. He wrote, in criticism of the technology behind ChatGPT, that the human mind is NOT “a lumbering statistical engine for pattern matching, gorging on hundreds of terabytes of data.” Maybe. But maybe the universe doesn’t owe us interpretable laws (and we are glorified pattern-matching machines after all).

It’s underappreciated how far the humble neural network has come. After early theoretical critiques in the 1960s, neural approaches fell out of favor for nearly two decades; anyone working on machine learning was largely seen as a joke, dismissed for chasing a scientific dead end.

I had a stormy graduate career, where every week we would have a shouting match. I kept doing deals where I would say, ‘Okay let me do neural nets for another six months and I will prove to you they work.’ At the end of the six months, I would say, ‘Yeah, but I am almost there, give me another six months.’

The turning point came in 2012, when AlexNet, an image classification model, won an image classification benchmark known as ImageNet and became the watershed moment that convinced the broader ML community of the capacity for neural networks to scale. LLMs followed on as an even more prodigious success, exemplifying the necessity of data-driven learned simulators and launching the transformer architecture to well-deserved acclaim.

Attention is not all you need

The scaling laws transformed modeling in scientific domains as well–learned simulators are outperforming traditional physics-based methods in both accuracy and speed:

-

Weather forecasting relied on Numerical Weather Prediction for over 50 years—physics-based models simulating atmospheric dynamics. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) refined this into the gold standard, and their models served as the backbone for weather.com, national weather services, and Google Weather.

- In 2023, Google DeepMind’s GraphCast, a graph neural network, exceeded ECMWF’s accuracy while making 10-day forecasts in under a minute on a single TPU, compared to hours on a supercomputer for traditional methods.

-

Protein structure prediction tells an analogous story. AlphaFold2, created in 2021, directly maps amino acid sequence to structure, incorporating insights from evolutionary history encoded in multiple sequence alignments. It has since predicted structures for over 200 million proteins, covering essentially all known sequences.

-

Materials discovery was revolutionized when GNoME, DeepMind’s Graph Networks for Materials Exploration, discovered 2.2 million new crystal structures, a feat that previously required approximately 800 years of traditional experimental discovery.

To be clear, none of these successes came from raw observation of data. GraphCast was trained on the output of fifty years of physics-based weather modeling. AlphaFold’s alignments encode evolutionary constraints as a biological prior. GNoME’s active learning loop uses density functional theory as the ground-truth oracle. In each case, ML learned to approximate or accelerate existing scientific knowledge; the theory came first. Moreover, progress along these alternative ML approaches isn’t necessarily bundled with the advances in ML that drove ChatGPT–the transformer architecture and its legacy. GraphCast is a graph neural network. Research has shown hybrid architectures including state space models to be most effective for large-scale DNA modeling. Different domains may have different inductive biases and data structures relative to language.

TLDR: ChatGPT releases and Epoch evaluations are a spectacular horse race, but certainly not the only one to invest in. There’s a massive long tail of ML problems that the frontier labs (outside of DeepMind) have yet to invest in.

Slaves to the physical world

Biology is arguably where the simulator is both the most necessary and least developed. The accessibility of data in other domains is a largely solved problem. Weather had ERA5 reanalysis data—decades of global atmospheric observations, assimilated and quality-controlled, publicly available. For materials science, training data comes largely from DFT calculations, which are expensive but automatable.

But biology wet-lab data is slow, noisy, expensive, often proprietary, and has been historically impossible to translate to real world validity. Cell lines don’t reliably predict what will happen in humans and animal models fail constantly; over 90% of drugs that work in mice fail in human trials. Single experiments can cost millions of dollars over the course of months. Sequencing has become cheap, but sequencing is only one modality. Predicting gene expression from sequence is hard. Predicting protein function from structure is hard. Predicting drug efficacy from molecular interactions is very hard. Arguably, we don’t even know what the right data to collect looks like.

Noetik has distinguished themselves with a multimodal approach of training cancer world models on multiplex protein staining, spatial gene expression, DNA sequencing, and structural markers. Biohub has been racing to build diverse measurement tools across scales, from individual proteins to whole organisms. Generating data across a plurality of modalities for a plurality of models is the strategy of having no strategy (and it applies to the entire field of biology).

It’s even possible that holistic theories of biology will continue to evade us. If so, progress will look less like physics and more like engineering–narrow focuses on particular diseases, particular organs, particular modalities. The work is unglamorous and the timelines are long. We remain slaves to the physical world.

AGI AI for science timelines

So why not just wait for the LLMs to figure it out? There’s credible evidence that the big labs have invested direct effort into building AI scientists for ML research, a potential route towards recursive self improvement. But even if LLMs build or significantly accelerate the creation of accurate simulators, the scientist and simulator systems can still be distinguished on their technical basis, data requirements, and deployment timelines, which have tangible impacts on investment and policy. GPT-7 may very well have the cognitive capabilities to design digital twins that simulate human biology, but it will have been enabled by many other players already advancing the algorithms behind effective simulators and building automated data infrastructure. In the same way that ML for world models, voice, and image generation were pushed forward by ElevenLabs, Midjourney, and WorldLabs, among others, we should expect ML for science to be pushed forward by a plurality of efforts.

The scientist (LLMs for reasoning and synthesis) is being built by the frontier labs.

The simulator (domain-specific ML models) requires specialized architectures and domain expertise. DeepMind has done impressive work here, but it’s not their core business.

Data infrastructure (automated labs, high-throughput assays, simulation pipelines) requires capital-intensive physical facilities and years of iteration.

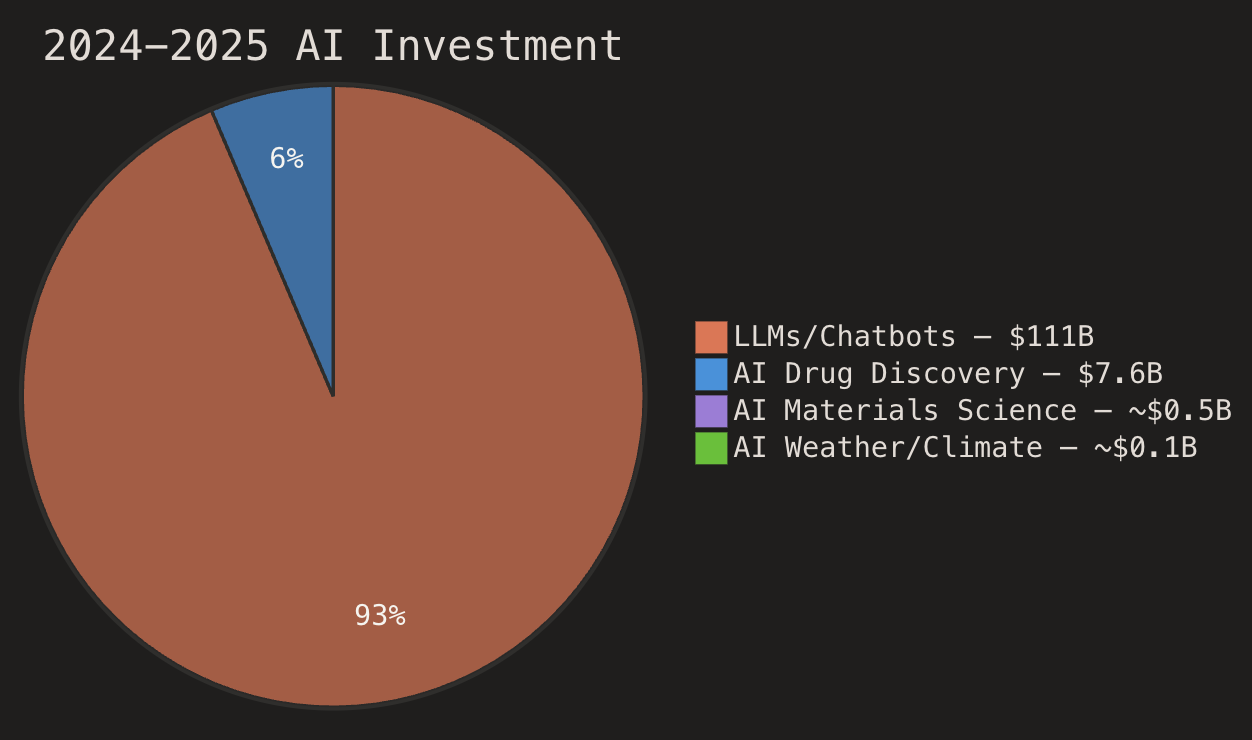

In 2024–2025, AI foundation model companies raised ~$111 billion—$31B in 2024 and $80B in 2025, with OpenAI and Anthropic alone capturing nearly 14% of all global venture capital in 2025. Meanwhile, AI drug discovery totaled ~$7.6 billion ($3.8B in 2024, $3.8B in 2025), and AI for materials science and weather/climate together attracted roughly $500M-$1B in 2024-2025.

There are already a few companies that are betting on this thesis for AI-driven scientific discovery, but the funding landscape remains arid. Lila Sciences, backed by Flagship Pioneering, is building “AI Science Factories”—automated labs where AI designs experiments, robots execute them, and results feed directly back into model training. Periodic Labs, founded by former OpenAI and DeepMind researchers, combines AI models with automated synthesis to create new materials.

Unless Anthropic starts building protein folding models, we shouldn’t expect them to solve diseases. Unless OpenAI starts building geospatial models, we shouldn’t expect them to become frontier weather forecasters. The big labs are focused on intelligence—reasoning, long context, tool use. Domain-specific simulation and data collection are massive undertakings that lie outside their core competencies and business models.

The discourse is focused on AGI timelines and the scientist’s capacity to reason. The work that will cure diseases and discover materials is more specific, more pluralistic, and more bottlenecked by the physical world.

Melissa Du is a Research Engineer at Fundamental Research Labs and is on X and on Substack. Give her a follow!